YaPhoto 2017: a curatorial debrief

by christine eyene

YaPhoto – Yaounde Photo Network held its 2017 events in Yaounde from 27 November to 2 December. Entitled Picturing the Present, the proposed theme sought to examine the local photographic gaze, question image-making processes and address the gaps between society and visual representation through the work of Cameroonian photographers. Conceived as an ‘expo-lab’ and creative hub set up at OTHNI – a Yaounde-based multidisciplinary experimental art space – the programme included a photography exhibition, video art screenings, portfolio reviews, and a panel discussion on the state of Cameroonian photography today.

The exhibition presented works by Romuald Dikoumé, Blaise Djilo, Wilfried Nakeu, Yvon Ngassam and Yaounde-based French photographer Sarah Tchouatcha. While Dikoumé’s and Nakeu’s images were a selection from a work-in-progress focusing on performative bodies (with figures covered in soil in Dikoume’s work or pages of magazines in Nakeu’s), Djilo and Ngassam’s were much more advanced projects. Blaise Djilo’s Feou Kake series invites the viewers into the atmosphere of the parade marking the harvest celebrations of the Tupuri people between the North of Cameroon and Chad. These unique images show the persistence of traditions in contemporary times, with an interesting nod to the gender fluidity shown by some of the parade participants, with some of the men seen wearing female accessories, like a bra or a belt to cover their ‘breast’, as they embody female figures.

Yvon Ngassam’s Bandjoun series – the outcome of a residency at the famous art centre Bandjoun Station created by acclaimed Cameroonian artist Barthélémy Toguo – takes the viewer on a journey across the various aspects of life in the West Cameroonian chiefdom. The photographs are complemented with short video documentaries, one of which was presented during the Digital Africa screening.

Female photography practice also had an important place in the display. Sarah Tchouatcha’s Ablutions, referring to rituals of purification with water, highlighted a particular object throughout her series – the plastic tea pot – in the manner of a still life. Anne Fontaine’s Émeutes (Riots), an installation of kaleidoscopic images printed on fabric exploring the aesthetics of social unrest while conjuring wax motifs, was spread across the gallery space, on the walls or displayed so as to give the fabric volume, on props like a wheel or a fallen ladder conveying the aftermath of a scene of disturbance.

Fontaine’s presence was part of a spotlight on arts from the Indian Ocean as the result of studio visits made last April in Reunion Island. This extended to the video art programme with the screening of Île de France by British-based Mauritian artist Shiraz Bayjoo, one of the announced artists of the next Dak’Art Biennial. His film is an immersive non-narrative piece, focusing on objects, architecture and environments acting as historical images or documents revealing encounters between Mauritius and its colonial past. Also hailing from the region, was Mounir Allaoui whose short videos looking at modern slavery or the act of braiding African hair are set within a Comorian context.

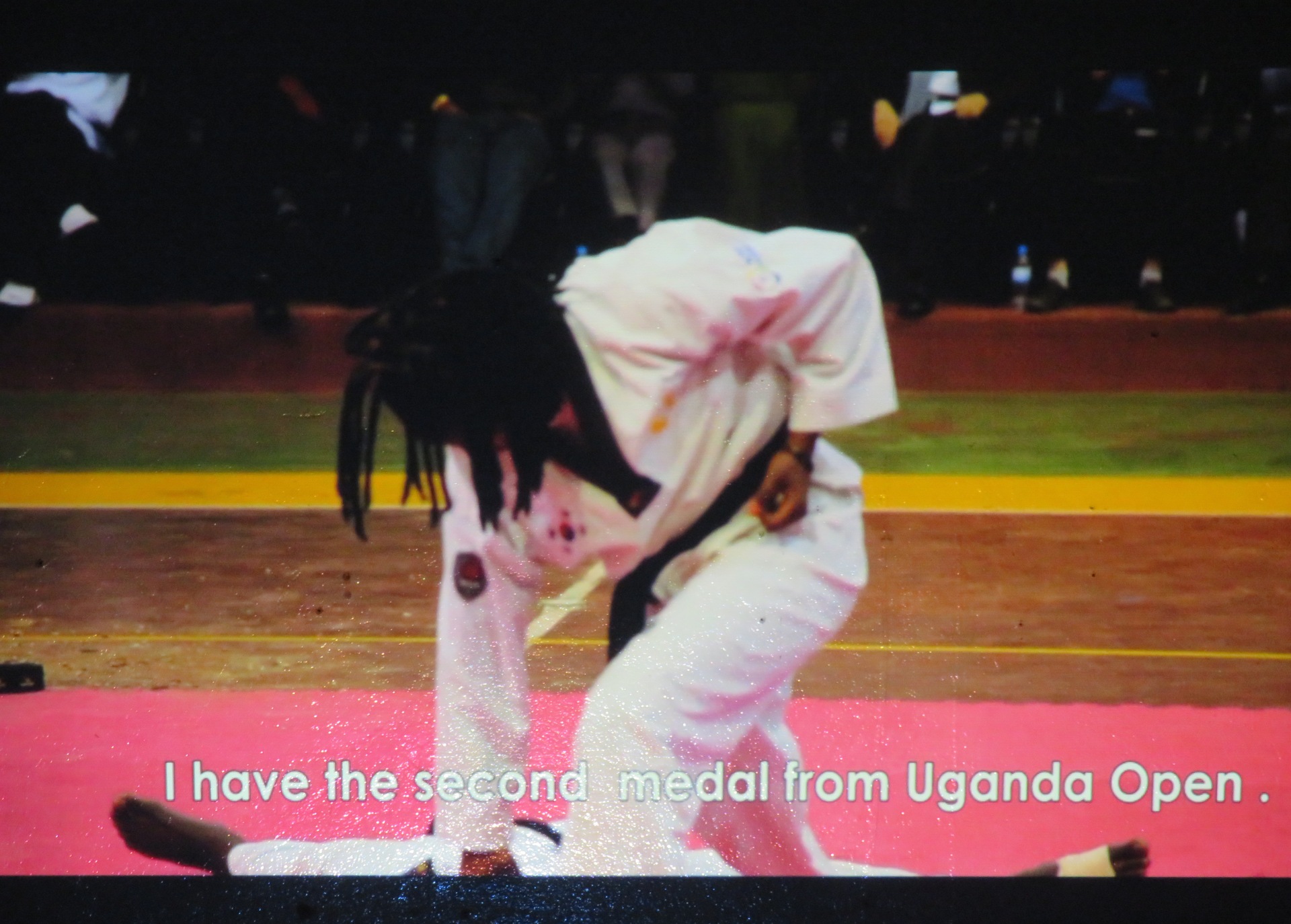

The videos presented as part of the Digital Africa screenings at OTHNI and Musée la Blackitude included works by: Ruy Cézar Campos (Brazil), Rehema Chachage (Tanzania), Edem Dotse (Ghana) & SUTRA (UK), Megan-Leigh Heilig (South Africa), Onyeka Igwe (UK), Mouna Jemal Siala (Tunisia), Emo de Medeiros (Benin-France), Danielle WaKyengo O’Neill (South Africa), Yvon Ngassam (Cameroon), Jean-Baptiste Nyabyenda (Rwanda), Saïd Raïs (Morocco) and Breeze Yoko (South Africa). The projections were an opportunity for the local audience to discover artists and works that had never been presented in Cameroon before. They were also meant to broaden Yaounde’s artistic offerings, trigger curiosity, and contribute to give inspiration to local image-makers.

In addition to the portfolio reviews aimed at emerging photographers was organised a round table on the state of photography in Cameroon. The discussion brought together photographers Rodrig Mbock and Yvon Ngassam, Madeleine Mbida, artist and co-founder of Nkongsamba Photography Festival, Parfait Tabapsi, founding editor of Cameroon’s cultural magazine Mosaïques and myself as organiser of YaPhoto 2017.

Among the key points addressed in the conversation was the observation that numerous aspects of contemporary life in Cameroon were absent from the local photographic register. There is indeed a real gap between what is experienced across Cameroon’s diverse societies and actual visual production. Beyond commercial photography or institutional assignments – that in no way engage in any form of criticality, enquiry or visual essay – fine art photography and photojournalism will only gain ground in Cameroonian lens-based practices once the visual spectrum is broadened and subject-matters explored in-depth.

While it is generally assumed that new technologies, and the proliferation of online platforms dedicated to photography, have the potential to foster a more socially-engaged imagery, this is actually not the case in Cameroon. As a matter of fact, it is worth noting that the beginning of YaPhoto’s pilot phase, that started in November 2016, happens to coincide with the early days of what is known as the Anglophone crisis. To my knowledge, neither these events nor their effect on the country as a whole – to which they are in fact an echo chamber – seem to have filtered through the gaze of, and images produced by, local creative photographers. Neither in the photojournalistic genre developed in South Africa during the anti-Apartheid struggle, nor in the form of anonymous documentation like in the case of Syrian collective Abounaddara. Not even in a conceptual manner as suggested by Anne Fontaine’s turning of scenes of social unrest into visual motifs.

In this respect, one has to seriously question the silence of photography and other visual art practices for that matter. Especially in a country that, some fear, could be on the brink of civil war should the lack of dialogue and repression continue to prevail. Photography, a medium historically known for being a window opened onto the world, hardly says anything of the visual registers of a country which presence is paradoxically so imposing on the African and global art scene when it comes to curatorial practice.

It is elsewhere that questioning and criticality are to be found. Notably in the work and discourses of filmmakers like Jean-Pierre Bekolo whose film Naked Reality (2016) was screened at Sita Bella auditorium as part of the Goethe-Institut Kamerun cinema programme entitled Vivre Ensemble|Living Together curated by Enoka Ayemba. Among the selection of films, that also included Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro (2016), was shown the very compelling Chef! (Chief!) by Cameroonian filmmaker Jean-Marie Teno. This 1999 documentary is a gutsy take on how decades of failed governance have sustained a trickle-down system of subjugation from the very top to those with the slightest power, be they the villagers exerting forms of mob justice violating human rights, women’s oppression by their husband sanctioned by marriage as an institution, or the dramatic crushing of opposition in a seemingly democratic country. In light of the country’s current situation, this documentary has not lost a single inch of currency. It is as relevant today as it was when it was first produced eighteen years ago.

Cameroonian photographers would gain much in engaging with, or revisiting, the practice of those who have contributed to create an invaluable visual heritage for the country. If the history of Cameroonian photography is not always readily accessible, contemporary auteur films and videos are. Cinematography, composition, technique, it’s all part of the same visual language and landscape. And it’s all there, available to those who seek.

But before that, first and foremost, observing the world around us, our society, and questioning should be the prime ingredients to develop the discourse that precedes the making of an image. This is the prerequisite of an engaged photography practice and should be the first concern, well before contemplating applying to major international photography events or multiplying local photography festivals.

In the current Cameroonian climate, photography training can only be efficient provided there is a form of critical introspection.

This is most probably one of the aspects Yaounde Photo Network is set to develop in the project’s next phase.

Visit YaPhoto 2017 page.

Click on any image to view the photo gallery

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email this to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)